The Best and Worst States for Elder Fraud in 2021

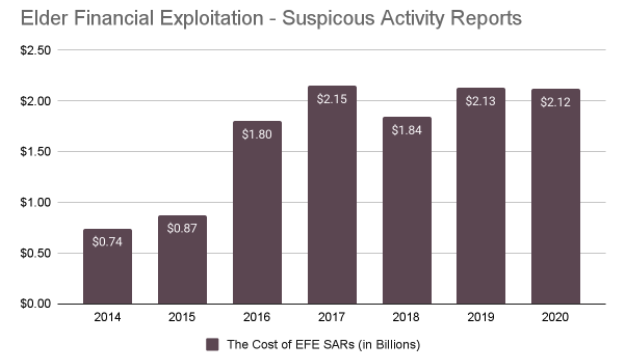

Fraud is a serious and growing problem in the US. According to a report from the FTC, consumers reported $3.3 Billion in fraud in 2020 – up from $1.8 Billion in 2019. It should be no surprise that seniors continue to face a higher risk, but what may be surprising is just how much more money seniors are losing annually in the US. Based on data from just one of the agencies that track fraud (Suspicious Activity Reports or SARs) collected by the US Treasury Department), elder fraud reports have risen by 186% between 2014 and 2020 – this represents an increase of $1.4 billion dollars lost to elder financial exploitation on a yearly basis (based on the estimated amount per SAR of $34,200).

To put that into perspective, fraud, in general, has risen by 125% (based on the same SAR data) – substantially less than the 186% increase in elder fraud, underscoring the increased danger to seniors and older adults. “There are a lot of factors that cause older adults to be at an increased risk for financial exploitation,” says Marci Lobel-Esrig, Founder, CEO and General Counsel of SilverBills. “One of the issues is that older adults are often more reliant on phone calls as a means of communication. Fraudsters use phone calls to entrap older adults into falling for scams, such as the ‘grandparent scam.’”

Not all states carry the same risk for seniors to be targeted for fraud. Based on the research done by SeniorHousingNet, we’ve found that seniors in Utah, Nevada, and Colorado face the highest risk for elder fraud, while New Hampshire, West Virginia, and Kentucky face the lowest comparative risk.

Read on for more information about the best and worst states (including the full ranking), helpful tips on avoiding common elder fraud scams, and a full list of elder fraud reporting agencies for all 50 states.

Methodology

In order to rank each state, we used a variety of data points from three different reporting agencies. Note that these three sources don’t represent the entirety of all fraud committed or even reported (some states have their own reporting methods outside of the three used here). We chose to use these three metrics for our research because they were available for all 50 states.

The three different reporting agencies were each used as a core metric, with two of the three core metrics made of two sub-metrics each. To arrive at the final score, we combined the scores from all three core metrics and weighted each to get the total score.

Note: For all tables and data points in this study, lower scores are always better and mean that there is less reported fraud.

As stated above, the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network collects SARs for all 50 states. The group collects and reports data on many different categories of fraud, but the one we used for this study is “Elder Financial Exploitation” (EFE). This category was created to specifically identify suspected cases of fraud against the elderly.

There were two sub-metrics identified within this core metric: SARs per 10,000 Elder Population, and Amount Lost Per Capita. While we display both for context, the latter is an estimated amount based on the total number of SARs (the average cost of each SAR is $34,200), so we did not use this sub-metric for final score calculations. The data used in this study is from 2020.

IC3 is run by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and accepts, compiles, and analyzes internet crime complaints both from affected parties and third parties. IC3 releases annual internet crime reports, and the 2020 report was used for this ranking.

Using data from this report, we found the overall percentage of fraud (both number of victims and dollar amounts lost) committed against adults over the age of 60. We then applied those percentages to the tables that listed the total amounts lost and total number of victims for each state. We used the results of these calculations as two sub-metrics for this core metric (IC3 reported amounts lost per older adult and IC3 reported number of victims per 10,000 older adults)

The sub-metrics are expressed as per 10,000 elderly population for the number of victims, and the average amount lost per actual adult over the age of 60 in the state.

The Administration for Community Living maintains the National Ombudsman Report System (NORS) that logs the number of investigated complaints per state. This core metric did not have any sub-metrics and simply scores the number of investigated complaints relating to finances and property per 100,000 people over the age of 60.

Our Findings

The 10 States with the Least Risk of Elder Fraud

#1: New Hampshire

New Hampshire ranked as the state with the least risk of elder fraud in SeniorHousingNet’s 2021 Elder Fraud Study. Ranking in the top 11 for each of our metrics, its lowest ranking was the number of EFE SARs (per 10,000 elderly population) and the amount lost per capita (ranked 11th). Its best performance was the number of LTCO investigated reports per capita (ranked 2nd).

#2: West Virginia

Ranking second overall, West Virginia excelled in the ICS core metric. It ranked first overall for both the number of victims per 10,000 population (2.0), and the amount lost per capita ($2.82). The state ranked 13th for both of the other core metrics, which is why it dropped to second place overall.

#3: Kentucky

Coming in third with an overall score of just 9.3, Kentucky ranked particularly high for the number of EFE SARs per 10,000 population (and estimated total losses). The relatively low number of SARs meant that there was an average loss per older adult of only $20.90, which is the third-lowest. The state’s worst performance was in the number of LTCO investigate reports – the state ranked in the bottom half (35th) for this core metric, which caused it to fall to number three in the ranking.

| State | Ranking | Score | SARs Per 10,000 Elder Population | SARs Amount Lost Per Capita (60+) | ICS 60+ Victims (Per 10,000 Elder Population) | ICS Victims’ Losses Per Capita (60+) | LTCO Investigated Reports (Per 100,000 Elder Population) |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 4.9 | 6.8 | $23.18 | 2.3 | $4.07 | 5.0 |

| West Virginia | 2 | 6.1 | 7.0 | $23.99 | 2.0 | $2.82 | 9.0 |

| Kentucky | 3 | 9.3 | 6.1 | $20.90 | 2.5 | $3.50 | 17.0 |

| Michigan | 4 | 10.5 | 6.1 | $20.86 | 2.6 | $10.00 | 6.1 |

| Wisconsin | 5 | 11.0 | 7.1 | $24.25 | 2.1 | $7.41 | 7.7 |

| Louisiana | 6 | 11.8 | 6.6 | $22.48 | 2.7 | $7.47 | 10.7 |

| Tennessee | 7 | 13.6 | 6.7 | $22.98 | 3.6 | $7.48 | 6.7 |

| Maine | 8 | 13.7 | 5.8 | $19.94 | 4.0 | $5.26 | 16.0 |

| Alabama | 9 | 13.7 | 8.1 | $27.56 | 3.0 | $6.82 | 5.2 |

| Vermont | 10 | 14.4 | 6.7 | $22.97 | 2.2 | $6.98 | 21.6 |

The 10 States with the Most Risk for Elder Fraud

#50: Utah

Utah ranked as the worst state in SeniorHousingNet’s 2021 Report on Elder Fraud. It performed the worst in the ICS core metric, with the second-worst score for the amount lost to internet fraud per older adult (an average of $26.67 per older adult in the state). It ranked in the bottom 11 for all other metrics.

#49: Nevada

As the second-worst state for elder fraud, Nevada ranked in the bottom 12 for all metrics and had the overall worst score for the number of ICS victims per 10,000 elder population (12.3). It also ranked 46th overall for the number of LTCO investigations with 9.2 per 100,000 older adults.

#48: Colorado

With the third-worst overall score, Colorado was second-worst for the number of SARs – the estimated average loss per older adult in 2020 was $111.85 compared to the US average of $38.86. It also ranked in the bottom four on the ICS core metric, with an average loss to internet fraud of $24.46 per older adult in the state in 2019.

| State | Ranking | Score | SARs Per 10,000 Elder Population | SARs Amount Lost Per Capita (60+) | ICS 60+ Victims (Per 10,000 Elder Population) | ICS Victims’ Losses Per Capita (60+) | LTCO Investigated Reports (Per 100,000 Elder Population) |

| Utah | 50 | 44.2 | 17.6 | $60.15 | 5.5 | $26.67 | 20.6 |

| Nevada | 49 | 44.0 | 11.4 | $39.05 | 12.3 | $19.07 | 25.2 |

| Colorado | 48 | 43.9 | 32.7 | $111.85 | 4.7 | $24.64 | 19.3 |

| California | 47 | 43.2 | 13.7 | $46.87 | 7.3 | $22.34 | 22.3 |

| Alaska | 46 | 39.4 | 13.8 | $47.10 | 4.8 | $15.79 | 18.3 |

| North Dakota | 45 | 37.7 | 9.0 | $30.92 | 5.8 | $45.34 | 13.2 |

| Virginia | 44 | 36.4 | 23.5 | $80.49 | 4.7 | $15.69 | 11.0 |

| Ohio | 43 | 35.5 | 13.0 | $44.47 | 2.9 | $17.49 | 17.4 |

| Washington | 42 | 33.9 | 8.3 | $28.31 | 5.1 | $15.28 | 17.2 |

| Texas | 41 | 33.4 | 8.4 | $28.79 | 5.5 | $17.28 | 11.2 |

Full Ranking

Below, you can view the full results of our ranking, and see how your state compares to the rest of the nation.

| State | Ranking | Score | SARs Per 10,000 Elder Population | SARs Amount Lost Per Capita (60+) | ICS 60+ Victims (Per 10,000 Elder Population) | ICS Victims’ Losses Per Capita (60+) | LTCO Investigated Reports (Per 100,000 Elder Population) |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 4.9 | 6.8 | $23.18 | 2.3 | $4.07 | 5.0 |

| West Virginia | 2 | 6.1 | 7.0 | $23.99 | 2.0 | $2.82 | 9.0 |

| Kentucky | 3 | 9.3 | 6.1 | $20.90 | 2.5 | $3.50 | 17.0 |

| Michigan | 4 | 10.5 | 6.1 | $20.86 | 2.6 | $10.00 | 6.1 |

| Wisconsin | 5 | 11.0 | 7.1 | $24.25 | 2.1 | $7.41 | 7.7 |

| Louisiana | 6 | 11.8 | 6.6 | $22.48 | 2.7 | $7.47 | 10.7 |

| Tennessee | 7 | 13.6 | 6.7 | $22.98 | 3.6 | $7.48 | 6.7 |

| Maine | 8 | 13.7 | 5.8 | $19.94 | 4.0 | $5.26 | 16.0 |

| Alabama | 9 | 13.7 | 8.1 | $27.56 | 3.0 | $6.82 | 5.2 |

| Vermont | 10 | 14.4 | 6.7 | $22.97 | 2.2 | $6.98 | 21.6 |

| South Carolina | 11 | 15.8 | 7.1 | $24.20 | 2.4 | $5.81 | 21.8 |

| Mississippi | 12 | 15.8 | 7.4 | $25.29 | 2.8 | $7.85 | 10.3 |

| Idaho | 13 | 16.2 | 6.4 | $22.04 | 2.5 | $8.49 | 16.6 |

| Indiana | 14 | 16.2 | 8.1 | $27.70 | 3.3 | $6.81 | 7.5 |

| Arkansas | 15 | 18.7 | 9.2 | $31.30 | 2.5 | $7.10 | 11.1 |

| Wyoming | 16 | 19.7 | 6.8 | $23.28 | 4.5 | $10.83 | 7.2 |

| Iowa | 17 | 19.8 | 8.6 | $29.41 | 2.1 | $8.24 | 12.3 |

| Pennsylvania | 18 | 20.0 | 8.3 | $28.52 | 2.8 | $9.64 | 6.9 |

| South Dakota | 19 | 21.9 | 17.6 | $60.29 | 2.3 | $4.44 | 17.0 |

| Hawaii | 20 | 23.5 | 10.0 | $34.09 | 3.1 | $11.14 | 4.7 |

| Connecticut | 21 | 24.1 | 6.7 | $23.02 | 2.5 | $13.69 | 25.2 |

| Kansas | 22 | 24.1 | 9.2 | $31.60 | 3.7 | $8.41 | 10.2 |

| Florida | 23 | 24.8 | 7.1 | $24.22 | 7.4 | $14.63 | 6.5 |

| Arizona | 24 | 24.9 | 7.7 | $26.24 | 3.9 | $12.12 | 11.8 |

| Oklahoma | 25 | 25.7 | 8.1 | $27.62 | 4.4 | $6.94 | 27.3 |

| New Jersey | 26 | 25.8 | 6.6 | $22.46 | 11.6 | $13.94 | 11.8 |

| Illinois | 27 | 25.9 | 6.4 | $21.92 | 3.8 | $15.43 | 19.4 |

| Montana | 28 | 26.0 | 7.2 | $24.58 | 11.9 | $5.81 | 35.9 |

| Georgia | 29 | 27.7 | 8.4 | $28.74 | 4.6 | $13.56 | 9.5 |

| Oregon | 30 | 28.2 | 7.7 | $26.21 | 3.3 | $10.79 | 31.8 |

| New York | 31 | 28.3 | 7.5 | $25.55 | 5.0 | $26.66 | 6.5 |

| North Carolina | 32 | 28.5 | 19.4 | $66.42 | 2.8 | $8.46 | 14.4 |

| Delaware | 33 | 29.1 | 73.3 | $250.69 | 9.5 | $7.31 | 6.5 |

| New Mexico | 34 | 29.4 | 7.8 | $26.74 | 3.9 | $13.54 | 19.1 |

| Rhode Island | 35 | 29.6 | 23.3 | $79.74 | 2.8 | $8.49 | 14.0 |

| Minnesota | 36 | 30.0 | 11.2 | $38.15 | 3.0 | $13.25 | 15.5 |

| Massachusetts | 37 | 31.8 | 10.8 | $36.79 | 3.0 | $17.57 | 11.0 |

| Missouri | 38 | 32.5 | 9.2 | $31.61 | 2.8 | $23.07 | 13.6 |

| Nebraska | 39 | 32.5 | 14.4 | $49.33 | 9.0 | $7.97 | 14.3 |

| Maryland | 40 | 32.7 | 8.2 | $28.07 | 12.1 | $13.41 | 15.8 |

| Texas | 41 | 33.4 | 8.4 | $28.79 | 5.5 | $17.28 | 11.2 |

| Washington | 42 | 33.9 | 8.3 | $28.31 | 5.1 | $15.28 | 17.2 |

| Ohio | 43 | 35.5 | 13.0 | $44.47 | 2.9 | $17.49 | 17.4 |

| Virginia | 44 | 36.4 | 23.5 | $80.49 | 4.7 | $15.69 | 11.0 |

| North Dakota | 45 | 37.7 | 9.0 | $30.92 | 5.8 | $45.34 | 13.2 |

| Alaska | 46 | 39.4 | 13.8 | $47.10 | 4.8 | $15.79 | 18.3 |

| California | 47 | 43.2 | 13.7 | $46.87 | 7.3 | $22.34 | 22.3 |

| Colorado | 48 | 43.9 | 32.7 | $111.85 | 4.7 | $24.64 | 19.3 |

| Nevada | 49 | 44.0 | 11.4 | $39.05 | 12.3 | $19.07 | 25.2 |

| Utah | 50 | 44.2 | 17.6 | $60.15 | 5.5 | $26.67 | 20.6 |

Common Elder Fraud Scams and How to Avoid Them

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, millions of elderly Americans experience an elder fraud scam each year. Unfortunately, seniors tend to be a popular target for scammers. Older adults may be less tech-savvy than younger people and may not know when a website, or online “friend,” is legitimate. They’re also more likely to have a lifetime of savings or own significant assets, making the potential gain for scammers greater.

And, as scammers understand, elderly people may be less likely to report the fraud out of fear that their family will lose confidence in their abilities. This leads to many cases of elder fraud going unreported. And with the elderly population growing in the United States, this problem could continue to impact an increasing number of Americans.

Like with many things, the best defense against elder fraud is prevention. Below, we’ll explain some of the most common types of elder fraud scams so you can be aware of the schemes, as well as tips to avoid elder fraud scams.

Common Types of Elder Fraud

Some elder fraud scams have been around for decades, while others take advantage of modern technology. Both types of scams can be difficult to detect, especially if you’ve never heard about them before. Below, we provide a brief overview of some of the most common types of elder fraud to help you familiarize yourself with common scams. Our goal is for you to gain awareness of these scams so that you’ll be able to recognize them in the future.

Financial Exploitation

Unfortunately, one of the most common types of elder fraud scams is financial exploitation from a family caregiver or other close friend or relative. In these situations, a senior’s family member or caregiver will extort money from the senior by writing false checks from the senior’s account, stealing their ATM card and making withdrawals, or by some other means. In severe cases, one may convince the senior to sign over ownership of significant assets such as their home.

This type of scammer takes advantage of the older person’s trust, and possibly cognitive decline. This also means that seniors may be more hesitant to report the fraud out of shame or wanting to avoid family confrontation. As Ms. Lobel-Esrig, CEO of SilverBills explains, victims of this kind of exploitation “may be reliant on the criminal and may not believe that the benefit of reporting outweighs the negatives of further impairing the relationship.”

Romance Scams

Modern romance scams, also called “catfishing” scams, occur when scammers create online profiles for false identities, then use these profiles to contact and strike up relationships with other people online. The goal of catfishers when it comes to elder fraud is often to convince the senior to buy them expensive items, send them large sums of money, or in extreme cases, provide them with their bank account information or sign over large assets. These scammers take advantage of the fact that seniors may be lonely and desire companionship. They also know that seniors may be less tech-savvy than younger people, and thus less likely to realize the “catfish” is not who they say they are.

Technology Support Scams

Another modern elder fraud scheme is the technology support scam. In these scenarios, scammers try to convince their targets that there is something wrong with their computer or cell phone, like a virus. Then, they ask the person to pay for services to fix the problem that does not exist.

Tech support scammers may target seniors via phone calls, pretending to be a representative from a major technology company. Or, they may use online advertisements or computer pop-ups designed to look like a warning message from the device. According to the Federal Trade Commission, scammers often specifically ask for payment via a wire transfer, gift card, and other forms of payment that are very hard to reverse.

Lottery or Sweepstakes Fraud

This type of fraud involves the scammer calling or emailing their target saying that they’ve won a big lottery or sweepstakes prize. They’ll then try to extort people by obtaining their personal information under the guise of sending the payment or prize, or telling the “winner” that they must pay a small fee to the caller to process their winnings and obtain their prize. In both cases, these scammers take advantage of the excitement of winning a prize and catching people off guard, so the target may not be as receptive to the strange requests of the caller.

Home Maintenance and Repair Scams

These scammers claim to be representatives for a home repair or home maintenance service, and erroneously state that the senior’s home needs repairs or maintenance work. Sometimes the scammers go so far as to use fear tactics and claim that the repairs are necessary for safety. Typically, the scammers require the senior to pay up-front for the repairs, saying they’ll return shortly to complete the work, but never do. Other times, the scammers will actually enter the home and steal physical belongings while they’re supposed to be making repairs.

As a rule of thumb, the National Consumers League recommends always checking a contractor’s references before agreeing to let them into your home and never paying for service in full up-front, especially if you haven’t had a chance to check the legitimacy of the person’s services.

False Advertisement Scams

Scammers may attempt to extort money from seniors by creating advertisements for services that do not exist, with the goal of getting seniors to pay for the non-existent service. The services are often especially relevant to seniors, such as reverse mortgages and credit repair. Because these services do exist and can be legitimate, it can be tough to detect when an advertisement is for a scam service, especially for older adults who may be less familiar with online ads.

Medical Scams

Elderly adults, unfortunately, also are often targets for Medical-related scams. A common one is Medicare fraud, which involves a scammer claiming to be a representative from Medicare to try to obtain a senior’s personal information over the phone. They may use this information to financially exploit the senior, or even commit identity theft.

Recently, there have been instances of Covid-19 vaccine scams, which took advantage of people’s eagerness to get the vaccine. These scammers would ask their targets for payment to be placed on a waiting list that did not exist, or create fake vaccine sign-up websites that required payment to sign up for a vaccine time slot.

How to Avoid Elder Fraud Scams

There is no way to prevent elder fraud completely; even the wisest people sometimes get caught up in a scam. However, certain behaviors you can implement can protect you from scammers and help you identify elder fraud scams before it’s too late.

The following list contains general tips for how to avoid elder fraud scams like the ones discussed above. If you’re a caregiver of a senior or have an elderly loved one, you can help them avoid elder fraud by making sure they know the following best practices for avoiding scams.

- Educate Yourself: Awareness of the common types of elder fraud scams is the first step to protecting yourself from them. Familiarize yourself with the types of scams explained above so that you can identify them if a scammer ever targets you.

- Protect Your Information: Be wary of online forms, phone calls, or in-person visitors who claim to need your personal information, such as your social security number, birthday, and financial accounts. If the business requesting the information is legitimate, there should be no problem if you take your time or ask to call them back before providing it to them. If you’re told that you must provide your information on the spot or there will be some negative consequences, it’s a sign that it’s a scam.

- Take Preventive Action: Scammers often use phone calls to target victims. One way to prevent being a target of such fraud is by adding your number to the National Do Not Call Registry, which blocks telemarketers from calling you. While it doesn’t block your number from all potential scammers, it does help reduce the pool.

- Do Background Research: If approached by someone who’d like to work on your house or offer any other type of services, do some background research on the person and company before giving them any personal information or money or letting them into your home.

- Be Wary of Free Prizes: When it comes to avoiding scams, a good rule of thumb is that if it seems too good to be true, it probably is. Scammers try to take advantage of one’s excitement the moment they hear they’ve won a big prize. If someone presents you with a prize, don’t give them any information or money until you’ve confirmed its legitimacy. This is especially true if you have no recollection of entering a sweepstakes or lottery.

- Double-Check for Small Differences: If you’re completing a transaction or payment online, double-check the URL of the page to ensure it’s legitimate. Some scammers set up fake websites that look like duplicates of the real thing, but with slight differences to the URL, like a misspelling of the company name. Any spelling errors on the web page or in a suspicious email can also be a sign that the person or business is not legitimate.

How to Get Help with Suspected Elder Fraud

Millions of elderly Americans are involved in elder fraud scams each year, but many cases go unreported. Seniors may feel embarrassed, or worry what others will think if they tell them they’ve been defrauded. It can also simply be very overwhelming, and people may not know where to turn after they’ve been scammed.

If you suspect that yourself or a loved one has been a victim of elder fraud, you can always report it to the National Elder Fraud Hotline. Launched in March 2020 and managed by the National Office for Victims of Crime, the hotline connects callers with a case manager who will assist with the reporting process and provide any other helpful resources. You can reach the National Elder Fraud Hotline by calling 833–372–8311.

Below, we’ve compiled the contact information for each state’s elder fraud reporting service. Click on your state on the map below to view the phone number and website where you can report elder fraud in your state.